Noah Moroze

Kronos: Proving Open-source Hardware Secure

Written on February 17th, 2021 - 18 minute readI recently completed my MEng thesis, Kronos: Verifying leak-free reset for a system-on-chip with multiple clock domains. For this thesis, I built a system called Kronos that formally verifies a security property for hardware based on OpenTitan, an existing open-source project.

This blog post summarizes what my labmates and I worked on, and highlights some of the most interesting and important pieces of this project: it describes how we actually prove that hardware is secure, and it explains a new technique we came up with for reasoning about circuits with multiple clock inputs. This post also goes over some of our final results, including changes we had to make to our hardware for security purposes and how we were able to contribute back to OpenTitan!

Background

People often rely on computers for making security-critical transactions, such as transferring money between bank accounts. However, modern computer systems are complicated, consisting of sophisticated hardware and operating systems. Such a complex system is bound to have bugs that compromise security.

One way to get a higher degree of security is to factor out security-critical components to a separate, simpler device that can be more easily audited. For example, the Trezor cryptocurrency hardware wallet is a dedicated device for securely managing cryptocurrencies. Kronos is based on a project called Notary, another example of such a device. Notary is used for secure transaction approval – imagine a USB stick that can be plugged into a computer and used to authorize important transactions, such as sending Bitcoin or transferring money between bank accounts. Notary can run multiple user-installed “approval agents” to support each of these different use cases.

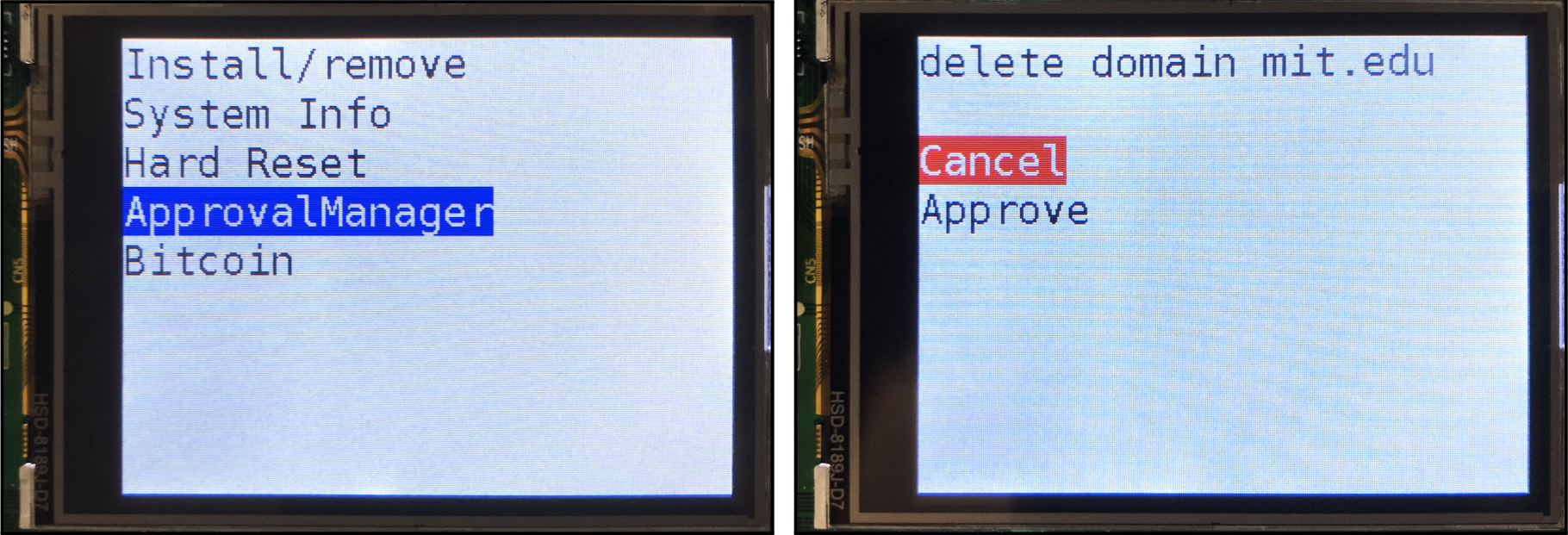

The menu in the Notary prototype. Image from the Notary paper.

The menu in the Notary prototype. Image from the Notary paper.

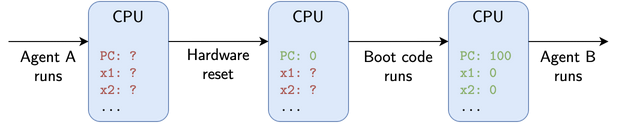

For security, Notary ensures that each agent is isolated from the others. This means, for example, that a banking agent that is malicious or compromised can’t steal the secret key from a Bitcoin agent and leak it to an attacker. To ensure isolation, Notary’s processor is reset to a fully deterministic starting state before switching agents. That way a malicious or compromised agent is never able to read secret data from previous agents, since it’s all been cleared before the next agent is run. Notary’s processor is reset in two steps: first, a signal is sent to an input on the chip, called the hardware reset line, which reinitializes parts of Notary’s state (registers and memories that store data) and causes it to begin executing special boot code. The boot code clears the rest of the state in the chip, putting it into a fully deterministic starting state.

Notary resets the state of its CPU in two steps between running each agent. First, the chip is hardware reset, which clears some data. Next, boot code runs, clearing the rest of the data. Note that ? represents all possible values, not literal Verilog don’t-care or X values.

This boot code is necessary because the hardware reset line itself does not actually clear all data in the chip. Rather, it clears just enough for the processor to correctly start executing code from a designated starting point. Without boot code to clear all data, agents would not be isolated – secrets from a previously running agent that are not cleared may be readable by an agent that runs in the future.

Notary formally verifies that the boot code puts the chip into a deterministic state, a property called “deterministic start.” Formal verification lets you prove that some system (either software or hardware) satisfies a particular property. Formal verification is important for security since many vulnerabilities may be subtle and difficult to capture by human analysis or testing. It’s also valuable to apply formal verification to hardware – many software systems have been verified, but the verification process often makes assumptions about underlying hardware, and these assumptions may have security implications. The widely-publicized Spectre and Meltdown exploits are an example of this: both attacks exploit vulnerabilities in the hardware of modern processors that violate assumptions about how an ideal processor should behave.

Research Goals

Notary is a good case study for hardware formal verification since it uses relatively simple hardware (compared to, say, the processor in your laptop) and requires a high degree of security. The Notary prototype is built around a very simple RISC-V processor, the PicoRV32. Our research started by asking if we can verify more complex hardware to implement an upgraded Notary with the same security guarantees.

There are many open-source RISC-V reference hardware designs freely available on the internet. We picked OpenTitan for the following reasons:

- OpenTitan uses the Ibex RISC-V processor, which seemed like an appropriate step up in complexity from the PicoRV32.

- OpenTitan is being developed by Google and lowRISC for use as a hardware root of trust, a security-critical application. This means it comes from a reliable source, and being designed with security in mind makes it feel appropriate for another high-security application.

After experimenting with OpenTitan for a bit, we identified two specific challenges that we would have to address to use it in a Notary-like design. These are the primary focus of my thesis.

Challenge 1: Non-resettable state

The first challenge is that OpenTitan contains storage components that cannot be cleared by boot code, meaning it cannot satisfy Notary’s deterministic start property. To use OpenTitan with minimal modifications to the hardware, we had to define a new property that provides the same isolation guarantees.

Challenge 2: Multiple clock inputs

The second challenge is that OpenTitan has multiple clock inputs, while Notary’s hardware only has one. To prove our security property, we had to develop a new proof technique that can handle multiple clocks.

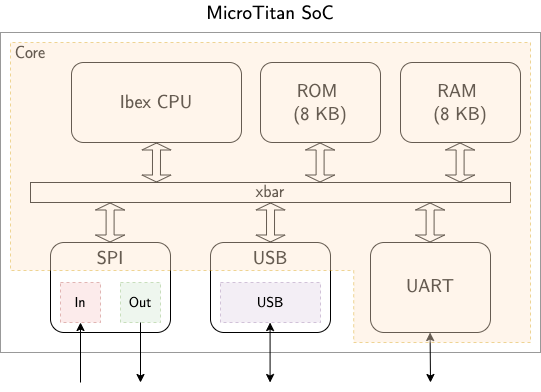

To manage the scope of the thesis, we focused on verifying a subset of OpenTitan’s hardware, which we call MicroTitan. We chose the components of this subset to be representative of these two key challenges. In particular, MicroTitan includes the SPI and USB I/O peripherals (which are the only OpenTitan components that have additional clock inputs) plus the baseline hardware necessary to actually run code.

Output determinism

Since MicroTitan cannot satisfy deterministic start, we defined and verified a new property, called output determinism, that provides the same security guarantees. For a circuit to satisfy output determinism, its outputs must never depend on data that was present in the chip prior to the last reset. The distinction between deterministic start and output determinism is that deterministic start ensures that a circuit’s state does not contain secret data, while output determinism allows the state to contain secret data as long as it never reaches outputs. This is enough to achieve Notary’s security goals: if secret data never reaches outputs then it’s impossible for an attacker to actually observe the data.

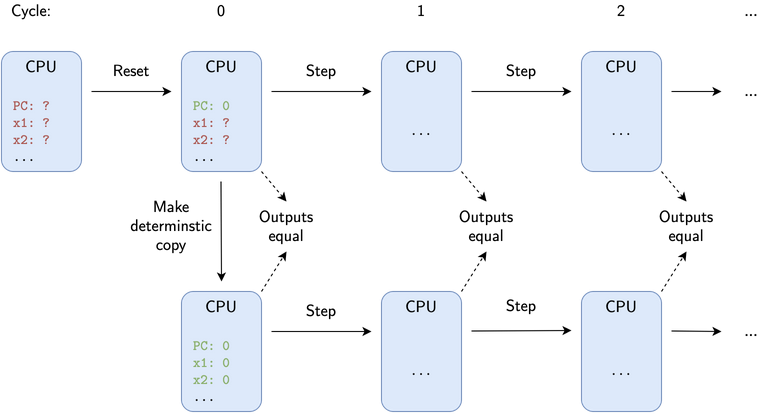

We can prove that a circuit satisfies output determinism by comparing the outputs of two instances of the circuit: one initialized normally, by asserting the reset line, and one that’s been deterministically initialized, where all of the state that contains data not initialized on reset is filled with zeros. This second instance must satisfy output determinism – it’s not possible for any data that was present in the chip prior to reset to leak to outputs, since this instance doesn’t contain any of this data in the first place!

Since this deterministically-initialized instance satisfies output determinism, we can show that the normal instance also satisfies output determinism if we can show that on every clock cycle, the two instances have equivalent outputs given the same inputs.

A circuit satisfies output determinism if its outputs are equivalent to a deterministically-initialized version of the circuit when stepped on the same set of inputs.

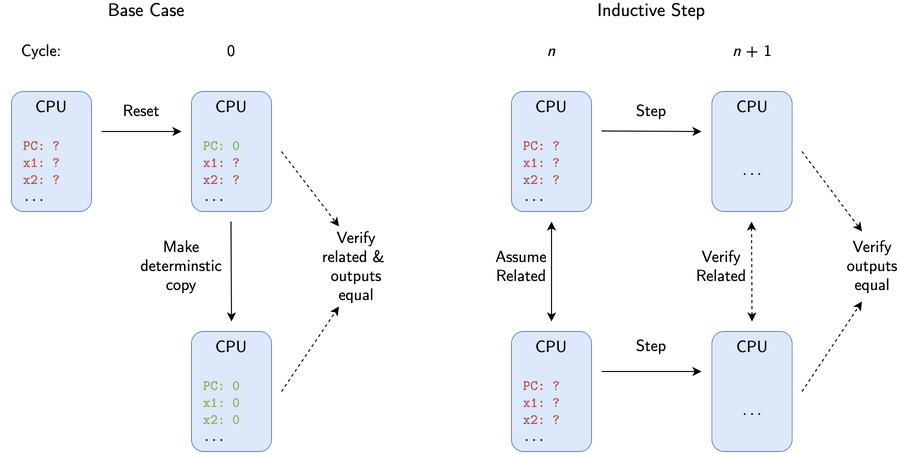

Proving this with code may seem infeasible since we have to show that the outputs would be the same even for an infinite sequence of circuit steps. However, we can turn this into a finite problem by using an inductive verification technique called simulation refinement. The idea is that we actually only need to prove two things:

- A base case, that this property holds for cycle 0 (the initial state of the circuit)

- An inductive step, that assuming our property holds for cycle $n$, it must also hold for cycle $n+1$

Proving these two claims implies that the property holds for all cycles $n$ without having to exhaustively show that this is the case.

Illustration of the two pieces of the inductive proof: the base case and the inductive step.

To prove the base case, we construct the two circuit instances as described above. We then verify that the outputs of each state are equal, and that they are related by a refinement relation. We define the refinement relation in the verification code – it depends on the specific circuit itself, but only certain definitions will allow the proof to succeed.

To prove the inductive step, we initialize two instances of the circuit with no constraints on possible register or memory values. We assume that these two states are related, and then step each one on the same set of inputs. We then verify that the resulting states have equivalent outputs and are still related.

Multiple clocks

To verify MicroTitan, we also had to handle multiple clock inputs. A clock input is what actually controls the execution of a stateful digital circuit. Each time a clock input undergoes a certain transition (often from a low to high voltage, or a “positive edge”), the circuit is updated based on its inputs. In a circuit with multiple clock domains, different pieces of the circuit are controlled by different clocks.

The key difficulty here is that there is no fixed relationship between the clocks in MicroTitan’s design. The clock for its USB peripheral is specified to run at 48 MHz, but the primary clock for the CPU has no specifically defined speed, and the clock for its SPI peripheral can be started and stopped by an external host at will.

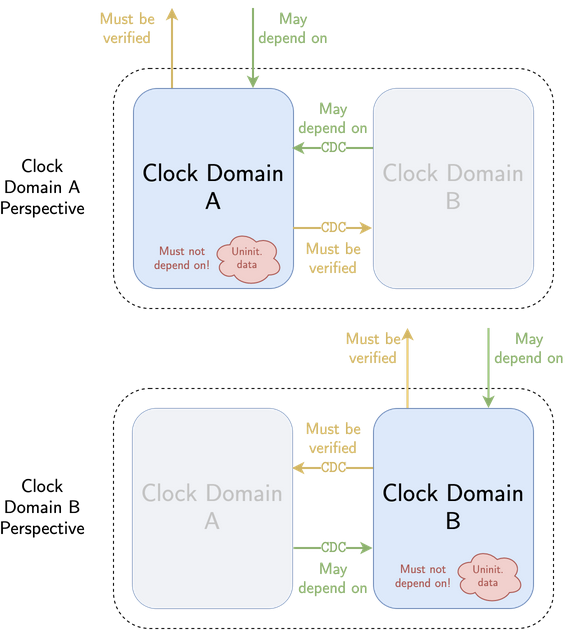

In order to address this challenge, Kronos uses modular output determinism, an approach we came up with that involves splitting up the circuit into one “subcircuit” per clock domain. The goal is then to prove an output determinism-like property for each subcircuit, which together imply that the circuit itself satisfies output determinism. By treating each clock domain as its own separate circuit, we can avoid the pitfalls of not being able to assume any relationship between each clock input, and instead treat each clock domain like its own single-clock circuit.

The main difference between subcircuit output determinism and “top-level” output determinism is that subcircuit output determinism cannot just consider the outputs of the subcircuit that correspond to outputs of the circuit itself, but must also consider the outputs the subcircuit uses to communicate with other clock domains. We call these outputs clock-domain crossing (CDC) outputs.

Modular output determinism for an example circuit with two clock domains. External and CDC outputs must both be verified to depend only on external and CDC inputs – they must not depend on uninitialized data.

This means that the external and CDC outputs of each subcircuit must be proven not to depend on uninitialized data. Since the subcircuits are verified not to leak uninitialized data to each other, outputs may depend on CDC inputs from other subcircuits. Each clock domain is effectively in a bubble outside of which uninitialized data cannot leak. Since the external outputs of all subcircuits combined comprise every external output of the circuit itself, proving that these outputs do not depend on uninitialized data implies the circuit as a whole satisfies output determinism.

Verification toolchain

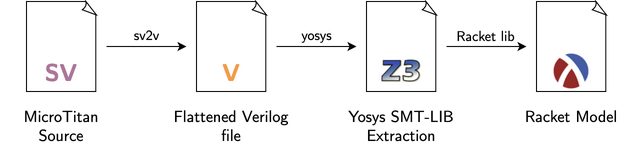

To implement these proof techniques, we simulate the circuit in a manner that maps exactly to the actual hardware behavior. This requires a toolchain for converting the hardware into a software model. This toolchain was originally used for Notary, and was modified and enhanced for Kronos.

The toolchain for producing a software model of the circuit.

The toolchain for producing a software model of the circuit.

The OpenTitan (and hence MicroTitan) hardware itself is written in the SystemVerilog hardware description language (HDL), a programming language for hardware. We feed the source for MicroTitan into a program called sv2v, which transpiles it into a simpler HDL called Verilog, which is passed along to the Yosys synthesis tool. Yosys transforms the hardware into a more primitive representation, and its output is interpreted by a custom Racket library. The resulting circuit model lets us write software in the Racket programming language that can initialize the circuit, simulate stepping its clocks with inputs we provide, and probe the data contained in its state or its outputs.

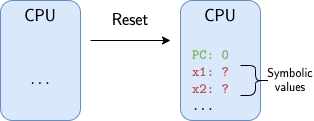

The other important software tool we use is Rosette, a library for “solver-aided programming” in Racket. Rosette supports symbolic execution, which lets us simulate how the circuit behaves when its state contains symbolic values, which are abstract values that can represent multiple numerical values at once. This lets us represent, for example, the fact that the circuit has multiple possible starting states, since any register uninitialized on reset will contain an unknown value based on whatever it was prior to reset. Without using symbolic execution, we’d have to verify every possible circuit starting state separately, which would be computationally infeasible.

The unknown state in the circuit after reset is represented in verification code using symbolic values.

Implementation

To implement modular output determinism for MicroTitan, we had to write verification code to prove output determinism for each of its four clock domains. The “core” clock domain contains the CPU, ROM/RAM, UART, and parts of the SPI and USB peripherals. The three “peripheral” clock domains, “SPI-in”, “SPI-out”, and “USB”, are each part of the peripheral their name implies.

A block diagram of MicroTitan with each of its four clock domains highlighted.

Core clock domain

To prove output determinism for the core clock domain, we were able to take advantage of the fact that this clock domain includes the CPU itself. This lets us reason about code execution. The verification script simulates the execution of boot code that resets as much state as possible (similar to Notary), then uses our output determinism verification technique to prove that the remaining, uninitialized state does not leak to outputs. The boot code is necessary since some state uninitialized on reset may leak to outputs if not explicitly reset by software (for example, the RAM).

Peripheral clock domains

On the other hand, proving output determinism for the three peripheral clock domains relies, for the most part, on the property being met inherently by the hardware. We found a few instances where the original OpenTitan hardware did not satisfy output determinism, requiring us to patch these issues in MicroTitan. The three main issues were:

- SPI TX leak: the SPI peripheral re-transmits a byte of previously transmitted data if a host begins a transaction before the CPU has had a chance to queue up new data for transmission. (patch)

- SPI RX leak: the SPI peripheral leaks almost a byte of previously received data to the CPU if the CPU intentionally toggles a specific configuration register in a certain way. (patch)

- Possible USB data leak: the USB may leak uninitialized data from a buffer if a certain transaction type is initiated by an external USB host at the right time. We are not 100% sure if this issue is actually exploitable, but we were unable to verify output determinism without patching it. (patch)

We found that all of the patches for these issues had a fairly minimal impact on the circuit size.

The most interesting output determinism violation was the SPI RX leak. This issue allows the CPU to read seven bits of uninitialized state left in the SPI peripheral prior to reset by toggling a configuration register at the right times. The SPI communication protocol receives data one bit at a time, and this configuration register controls the order in which bits are recombined to form full bytes of data. The register that stores these recombined bits in the hardware is left uninitialized on reset, meaning it initially contains whatever byte was last received via SPI. By toggling the configuration register in between every new bit that’s received, this register does not get completely filled with new data before the hardware counts that a full 8 bits of data have been received and sends the data off to the CPU. The following GIF illustrates how this works. The top animation shows normal operation with an LSB order, while the bottom animation shows what happens when the CPU toggles the order after receiving each bit.

Animation of the SPI RX leak. The red numbers indicate each bit, labelled by index, that is left over in the rx_data register from the previous execution. The green numbers are the indices of the new bits shifted in. Note that once the counter hits 8 bits received, rx_data will still contain the uninitialized bits 1 - 7 in the malicious case.

Verification stats

Overall, it takes about 3.5 hours to run Kronos’s verification code. The code consists of about 1,000 lines (not counting various libraries and utilities). Proving output determinism for the core clock domain takes more lines of code and accounts for almost all of the runtime since it involves simulating the execution of boot code over thousands of cycles. By comparison, proving output determinism for each peripheral clock domain simply involves proving the base case and inductive step.

| Clock domain | Lines of Code | Runtime |

|---|---|---|

| Core clock domain | 464 | 3.5 hours |

| USB | 303 | 41 seconds |

| SPI-in | 130 | 18 seconds |

| SPI-out | 128 | 18 seconds |

Impact on OpenTitan

Although we found multiple violations of output determinism in MicroTitan, these do not translate into security issues in OpenTitan itself given its intended application – the OpenTitan threat model makes different assumptions than Notary, including that data transmitted by I/O peripherals is never considered secret. However, this project did result in one change being upstreamed into OpenTitan, in order to patch its synchronous FIFO primitive to not leak data when empty. Although not required for their security purposes, this change was accepted in order to provide defense-in-depth.

Conclusion

Through Kronos, we showed MicroTitan provides the necessary security guarantees to be used in a secure Notary prototype. To do so, we defined a new security property called output determinism and an approach called modular output determinism to formally verify this property for a circuit with non-resettable state and multiple clock domains.

We used a custom toolchain to implement this formal verification approach for MicroTitan. The verification process revealed violations of output determinism in the open-source OpenTitan code MicroTitan is based on. We showed that these violations were limited to I/O peripherals, and could be easily patched to produce a circuit that satisfies output determinism. This process even gave us a chance to contribute back to hardening the security of OpenTitan itself.

Overall, Kronos is an interesting case study in verifying a security property at the hardware level, furthering prior work by addressing challenges that occur in realistic hardware. This is important for making strong security guarantees about systems without relying on assumptions about their underlying hardware.

More & acknowledgements

To see the code behind Kronos, check out the Github repo. To read about the project in more depth, see the thesis.

Thank you to my mentor Anish Athalye, who laid the groundwork for this research through Notary and guided me along the way, and thanks to Professors Frans Kaashoek and Nickolai Zeldovich for their support and guidance.

Thanks to Claire Nord for feedback on this post.